Mostra "Scollamenti" ottobre 2025

Antonio Carena's work is about linguistic or metaphysical operations, a critical analysis of a particular type of psychic structure when it frees itself from all syntax rules, or on the contrary, a sort of mental retaliation against the flooding of excessive modern and ancient rhetoric. All this set of reactions and counter-reactions is a moment of reflection and introspection on the possible destiny of contemporary art. This instrument of communication at its zero degree stands against nonsense (the "skies" could already appear as a zone of absolute freedom in which the artist invited people to place themselves in the brief pauses of their conscience). Now the signs are spaces of unexplored territory, open to nothingness but also to invitations for new inscriptions, they are a semantic inversion of a sky totally obscured by clouds or by the infinite subdivisions of the name. It is impossible to go further in our discourse since it covers many points of contemporary art. But what has happened in linguistics, where the classical immobility of words, through phonetics and glossematics, has been broken up by the investigation of Saussure or Hjelmslev or Trubetzkoy, it is logical that it should also happen in art, where the end of the image, here envisaged in these white signs, should also anticipate, through its syntactic shattering, the decay of rhetoric and the future rise of images that are still unlikely at the moment.

Janus, Presentation in the solo catalogue, Galleria II Fauno, Turin, November 1971.

Text by Barbara Aimar (thanks to Casa Museo Antonio Carena)

Story of Antonio Carena

Fashion keeps changing, but art is not a fashion; it is creativity capable of manifesting itself through unstoppable transformations, it is a research path “in progress”, it is the conquest of available space, it is... knowledge and the ability, each time, to destroy the propagandistic schemes of styles “in progress”, to freely express one’s imagination. Antonio Carena, who was born in 1925 and has always lived in Rivoli, was an exceptional character, with a unique vitality and irony, a twenty-year-old’s unconventional bearing with the ability to convey the joy of living and the love of “discussing art”. An artist with a capital A, he has always lived close enough to Turin to be able to examine its cultural ferments and sufficiently detached to be able to evaluate it with enough irony not to get involved in too strong or dubious situations.

Antonio Carena, part of the generation of artists formed in the difficult post-war period in Italy, in a Turin then united in the ideology of “reconstruction”, after an initial decorative practice within his family, he began his studies at the Accademia Albertina and he chose the Painting School held by Enrico Paulucci open to fluid and vibrant colourism. He was invited at just 25 to the 25th Venice Biennale in 1950, where he exhibited La Finestra of 1949. In those years he came in contact with the recent research of North American Action Painting and, fully accepting its innovations, he exhibited in 1951 at the Premio Dino Uberti at the Accademia Albertina the first Black Grates that characterised the existential crisis of 1950-53. Already then emerged the artist’s desire to let “what was seen through” and the desire, not yet explicit but strong, to want to “demolish” the commonplaces, the principles.

It was Michel Tapié who, as a sign of his esteem for the young artist, wrote the presentation text for his second exhibition in 1959. This represented a turning point in the artist’s work because his paintings were characterised by a diffused and dynamic brightness rippled by subtle and light aggregations of sand, an informal typology that was rather unusual in Turin and on the national scene. The French critic, who declared the need for a new experience, noted how Carena's paintings proposed a possible order, in tune with the new postulates, through a new constructive dimension.

The early 1960s coincided with his personal quest to go beyond painting, which led him towards an interest in the object dimension of the artistic artefact, emphasised by the emergence of American Pop Art.

Carena was one of the first Italian artists to work on the removal of parts of the object taken from the urban and industrial environment, focusing on its mirror image. He replaces the surface of the canvas with parts of the bodywork made into a mirror image; he "no longer paints” but presents and observes events that are reflected deformed on the surface of the industrial object, in equal integration with reality. This operation is carried forward by the films of 1964.

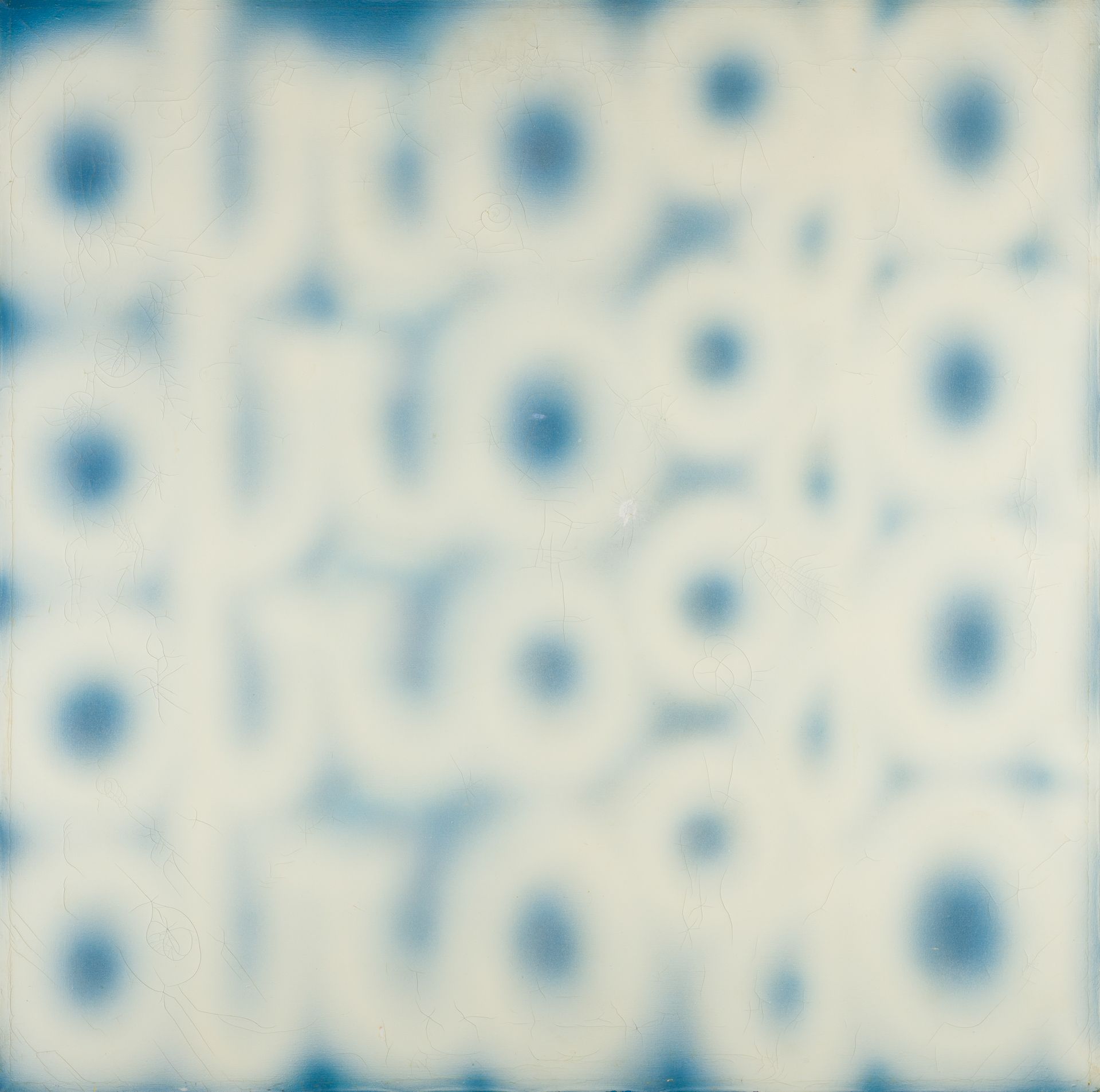

1965 was the year of the invention of his magnificent Cieli (Skies), trompe l'oeil paintings with an airbrush on metal sheet. An exemplary and isolated path after fifteen years of intense work passing through the international Informal movement: skies "more real than real", hyperrealist before time, of perverse and vertiginous Magrittian beauty, to be enjoyed in the urban dimension, in the privacy of city rooms.

The theme of the “cielo” [sky] became the obsessive and winking leitmotif of his work, and he coined neologisms for his images: “cielismo”, “cielagione”, “nuvolare” and others, making use of “the vocational technique of the carriage painter” ... Thus, with light and colour transmitted onto the canvas with an air brush, Carena creates the artifice of the “sky object in the foreground”, capable of emotionally attracting the observer.

Antonio Carena has “incielato” buildings all over Europe, where he has exported his talent, and carried out projects with and for important organisations over the years. He has frescoed the ceilings of the Accademia delle Belle Arti in Turin, decorated a Martini & Rossi building in Geneva, the Library of Palazzo dei Marchesi Spinola as well as the vaults of the Ministry of Culture in Paris, those of the renovated Juvarra's Castle in Rivoli and collaborated with Fiat on the ceiling cover in its Rome headquarters. He has created works of art of various sizes that have taken part in international exhibitions and events, winning prestigious prizes. He has combined this with his work as a teacher at the Art School first and then at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Cuneo.

Antonio Carena's sky above the staircase of Rivoli Castle was created by the artist in 1984, an integral part of the restoration carried out by architect Bruno.

Carena then presented some provocative oleographic views of the Matterhorn on skies crossed by cuts, frames and sections. He “captured”, “packaged”, “sliced”, “cut out” in frames and “enclosed” or boxed in perspex cubes his portions of skies. On the day of the inauguration of his solo exhibition at the gallery in Via Principe Amedeo, in 1967, he had parked a 500 car completely painted “a cielo” in front of the entrance, extending the assumption of the exhibition into the urban dimension.

After Cielo o finestra spancata sulla parete [Sky or wide-open window on the wall], Carena moved on to Cartelli [Signs] in 1970. The painting became a sign: a large sign with a pole, where holding the “air brush” he would write Parole Parole, or with his usual irony, Vogliamo Cieli Puliti, Attenzione Pittura Fresca e Immagina un po’ quello che vuoi [We want Clear Skies, Attention Fresh Paint and Imagine what you want].

Carena is the one who decided the distances between himself and the world and himself and the sky. Whether one remembers him in his garden-studio with a set of spray guns and compressors intent on vaporising clouds, or in a historic palace frescoing the vaults, one should not forget what he provocatively said: “I love clouding to denounce the sky to stop imitating me”. Carena has built a path listening to his inner chords. He lived honestly and stubbornly outside academic dictates, his interpretation of the world was anti-pictorial, especially in terms of the tools he used; he combined witty thinking and verbal jokes with calibrated and personal pictorial choices. This is another reason why he is one of the most important figures of 20th-century Italian art.